Few names in Indian architecture resonate as profoundly as Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, widely known as B.V. Doshi. A pioneer, philosopher, educator, and the first Indian architect to win the prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2018, Doshi’s work goes far beyond designing buildings—it reflects a deep commitment to social responsibility, cultural continuity, and sustainable living.

From intimate homes to sprawling urban projects, his architecture captures the spirit of India: layered, diverse, inclusive, and deeply humane. Among his many landmark works, the Aranya Low-Cost Housing Project in Indore stands out as a transformative model of social housing with dignity.

Early Life and Education

B.V. Doshi was born on August 26, 1927, in Pune, Maharashtra, into a family of traditional furniture makers. This early exposure to craft and material had a lasting impact on his architectural sensibility, embedding in him a lifelong appreciation for artisanry, structure, and the relationship between form and function.

Doshi studied architecture at Sir J.J. School of Architecture, Mumbai, and began his professional career during India’s formative years post-independence—a time charged with the energy of redefining cultural identity. In 1950, Doshi moved to Europe, where he worked under the legendary Le Corbusier in Paris for several years. He also collaborated with Louis Kahn, another influential figure in modern architecture, particularly on projects in India.

While these modernists shaped his architectural training, Doshi diverged from their often rigid and formalist approaches to develop a distinctive language—one that blended modernism with Indian traditions, climate, rituals, and community life.

Professional Journey and Contributions

On returning to India, Doshi worked with Corbusier on projects like the Mill Owners’ Association Building and Shodhan House in Ahmedabad. In 1956, he founded his own practice, Vastu Shilpa Consultants, which became the base for a career defined by both innovation and humility.

Doshi was also a visionary educator. He established the School of Architecture in Ahmedabad in 1962 (now CEPT University), fostering a new generation of architects who would go on to redefine Indian design thinking. His mentorship style emphasized exploration, dialogue, and social responsibility.

Throughout his long career, Doshi’s projects ranged from cultural institutions (like Tagore Memorial Hall, Ahmedabad), educational campuses (CEPT University, IIM Bangalore), to urban design and social housing. His work was always driven by a central belief: architecture is a living entity, shaped by people, place, and time.

Aranya Low-Cost Housing Project, Indore: Architecture as Social Equity

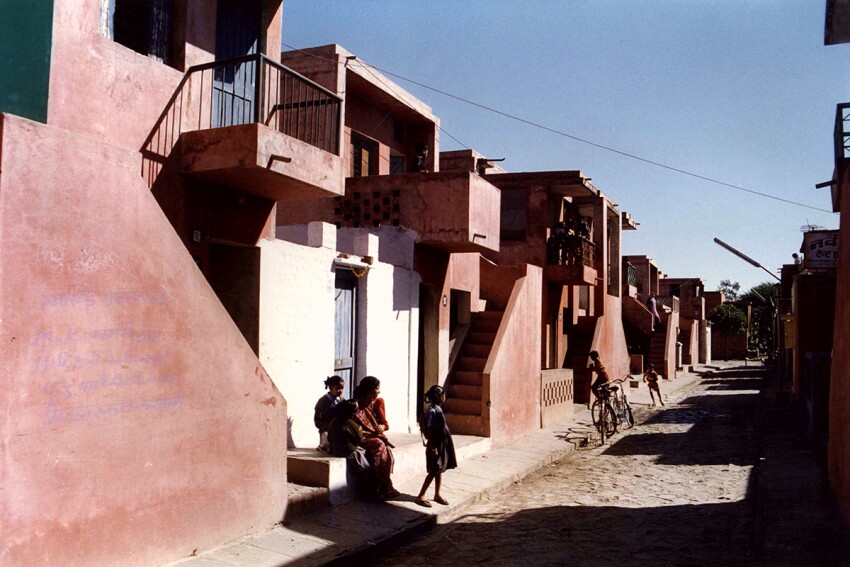

Perhaps the most celebrated example of Doshi’s architectural ethos is the Aranya Low-Cost Housing Project, designed in 1989 in Indore, Madhya Pradesh. It exemplifies his lifelong commitment to architecture that uplifts the underserved and engages deeply with local context and community needs.

The Context

In the 1980s, India was struggling with rapid urbanization and a growing shortage of affordable housing. The government launched schemes for economically weaker sections, but many failed due to poor planning and lack of long-term vision.

Doshi approached Aranya not as a charity project, but as a chance to reimagine urban housing. He believed that low-cost housing should not mean low-quality living. Everyone, regardless of income, deserved homes with dignity, flexibility, and connection to community life.

Design Philosophy and Planning

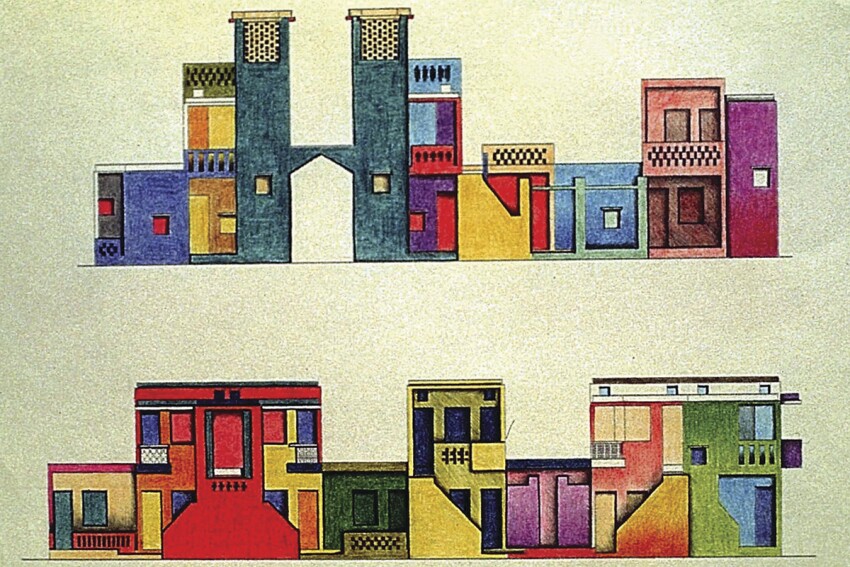

The Aranya project was developed for over 80,000 people across 6,500 dwellings, ranging from fully built houses to serviced plots with shared infrastructure. The “incremental housing” model allowed families to start with a basic unit and expand their homes over time, based on their means and needs.

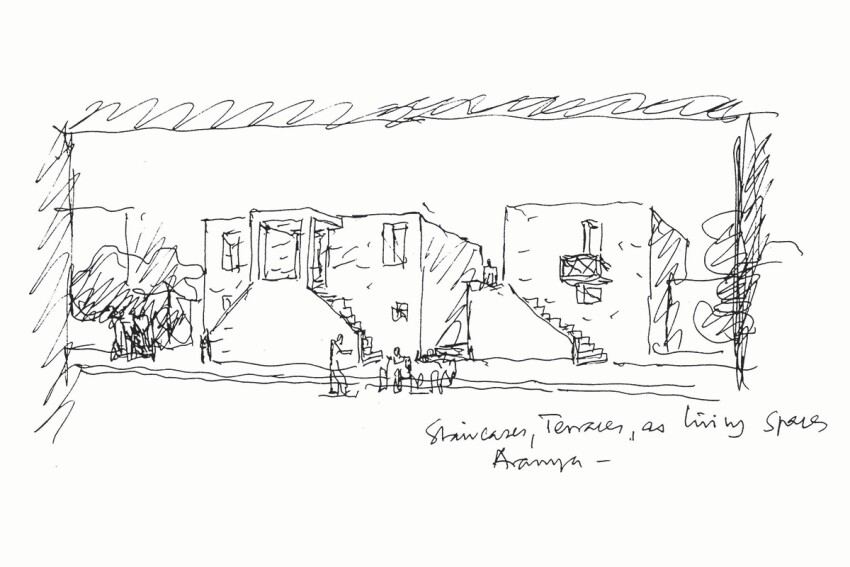

Doshi organized the layout around a central spine, with clusters of homes arranged along narrow streets, courtyards, and shaded paths. This generated a sense of neighborhood and encouraged informal interactions, much like traditional Indian towns.

Instead of imposing a fixed architectural form, Doshi designed a framework for life to grow—a canvas on which each family could paint their own story. Houses evolved organically, filled with personal touches, shops, workshops, and greenery.

Material and Sustainability

Aranya used locally available, low-cost materials and simple construction methods. The design emphasized natural ventilation, daylight, shared public spaces, and water management systems, making it environmentally sustainable as well as affordable.

What set the project apart wasn’t just its cost-effectiveness, but its human-centered design. There were no sterile rows of identical blocks. Each street had character, each corner an identity. Aranya felt alive—because it was built for and by the people who lived there.

Impact and Recognition

Over time, Aranya has evolved into a thriving urban neighborhood—a rare example of successful, scalable, people-driven housing. It proved that architecture could be a catalyst for empowerment, not just enclosure.

The project earned global recognition, including the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1995. When Doshi was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2018, Aranya was highlighted as a defining work that redefined how architecture could serve society.

Legacy and Influence

B.V. Doshi passed away in January 2023, but his legacy continues to shape architectural thinking in India and beyond. He was more than an architect—he was a cultural philosopher, a builder of institutions, and a mentor to generations.

His work challenged the notion that great architecture must be monumental or expensive. Instead, he believed that architecture is a backdrop for life, and the best buildings are those that enable people to flourish.

For Doshi, every project was a conversation—with the land, the climate, the people, and the culture. Whether designing a museum or a housing colony, his buildings invite participation, imagination, and community.

Conclusion

B.V. Doshi’s life and work remind us that architecture is not merely about structures—it is about society, empathy, and evolution. His Aranya Housing Project is not just a success story in low-cost housing—it is a blueprint for equitable urbanism, a testament to what architecture can achieve when it serves the many, not just the few.

In Doshi’s words:

“Architecture is not a building. It is a relationship between life and space.”

Through that lens, his legacy will continue to build hope, dignity, and belonging for generations to come.